In prison slang, ice time is short for isolation time, time spent in solitary confinement. Prison is all about time, about, as the phrase goes, doing time. About doing time in, come to think of it, the "cooler." If prison's the refrigerator, then isolation is the freezer. Everything slows down in the cold.

I went to the Broadmoor Sanctuary again last week. The temperature had moderated, and the snow had melted from the paths and meadows, but the marsh was still frozen over. I kneeled and peered over the edge of the boardwalk. I saw simulacra of summer -- the color-strewn expanse of a summer dress,

a green fan --

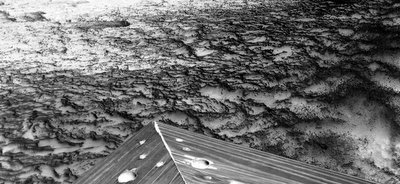

but mostly there was ice. Thick, imprisoning ice.

Expanses of ice best viewed in crime scene black-and-white.

There is an appetite for punishment afoot. In California an old, old man, a murderer scheduled for execution, asked for clemency. The Governor, once an actor in violent, thanatocentric films, declined. He witheld mercy. It seems odd to put this muscular man, this Terminator, in charge of something as delicate as mercy.

The prison warden, when asked why he'd denied the old, old man's request for no resuscitation were his heart to stop before the date of his scheduled death, explained, "At no point are we not going to value the sanctity of life. We would resuscitate him." There is no mercy in the warden's double negative. The math is clear.

The winter goes on and on. The worst is yet to come. It has snowed twice, three times, since my walk in the mild woods. My heart, which is so near I can feel it tap the bars of its cage, also seems to sleep faraway and deep in a dark ice cavern. Is there mercy in that paradox ?

On ice, time slows, space shrinks. The excruciating seconds creep along. The walls press in. Then, in a windowed room, in a little panopticon, almost an amphitheater, thick salts sluice into a vein and a heart quivers and stops. Serious, uniformed men and women stand around, some in medical white, one in clerical black, others in law and order blue or bureaucrat brown. Established protocols have been followed. The machinery of the state and of the law stands behind it all. A muscular man, once an actor in blood-drenched films, has given the nod.

A spectator raises a tentative hand. What is meant, he asks, reading from a small notebook, by cruel and unusual ?

Turtles are sleeping under the ice of the Broadmoor marsh. Their metabolism has slowed; their sleep is an imitation of death. Last summer I watched them paddling and sunning in the shallow, lily-stalked water. And now, although they are no more than 15 feet away, so close one could practically pry them out of mud and shake them awake, they seem impossibly remote. They sleep buried, side by side, in solitary confinement, in suspended animation. In the spring some will awaken, some will not. They seem to be trying to teach me something about time and mercy. I lean over the blank ice, close my eyes and listen.