I was the one who'd suggested we accompany my mother's body to the crematorium. It seemed right to shepherd this most immanent and important part of what she'd been to its last earthly appointment. So, Monday morning, I found myself in the back seat of my brother's car, traveling through the outskirts of Haverhill toward an establishment called Linnwood Crematory. Crematory: a noun that replaces the nazi-like stink of crematorium with a fresh whiff of dairy.

Her remains, the funeral director explained, would be placed in the retort. Note the absence in that sentence of body, undertaker, and oven; note, even, the conspicuous absence of an elegant, latinate mortician. We were in euphemism territory as well as in Haverhill, and it was bleak. I gazed out the car window at the post-industrial, suburban wasteland of fast food joints, filling stations and aging strip malls -- all with faux mansard roofs, it seemed, and all encrusted with grimy fin d'hiver snow -- and felt a deep, claustrophobic, all-pervading, almost overwhelming, spiritual nausea.

This is it, I thought, watching a garish pod of diners waddle out of MacDonald's, supersized shake cups in hand and straws in mouth. I sighed, not with carsickness, but with acedia, a thick, cold, pinkish slurry of apathy, despair and torpor that lodged, squirming, in my upper chest. See Christ in all persons ? I would prefer not to.

My mother, the funeral director said, had passed away. Now there was another euphemism, a fastidious one, practically Victorian. She had swooned, if you will, into the great beyond. I, myself, prefer died and it's pair of thudding D's. We'd watched at the her bedside for three days and two nights, my father, my brother and his wife, and myself. "Passed away" does not do full justice to the labor of dying.

There is a certain stately, liturgical grandeur to the list of diagnoses that had led, over two and half years, to my mother's death: Alzheimer's dementia, myocardial infarction, emphysema, pulmonary edema, methicillin-resistent staphylococcus aureus pneumonia, contrast nephropathy, ANCA positive polyangiitis, allergic interstitial nephritis, urosepsis, dehydration, aspiration. But the incarnational reality of her death -- the bewilderment, fear, pain, weakness, breathlessness -- resisted euphemism, be it Latinate, Hellenic or Victorian. During her last rehab stay in December she'd lost function -- strength, cognition, continence. At home the decline continued: her appetite failed, she developed strange, undiagnosed pains in all her limbs, and could barely rise from a chair or walk -- even with maximal help -- because of weakness, pain and fear. My devoted father tended her tirelessly; on February 15th she went to the hospital, and was discharged to hospice on the 19th, her white blood cell count on the rise and the sensitivities of the staph aureus that had infected her kidneys still pending. Henceforth test results -- all those numbers and reports that comprise the language in which I think about illness -- would be moot.

Beside my mother's bed during her last three days was a machine, an oxygen concentrator. It was, in keeping with hospice, a comfort measure, along with the all-important comfort kit, a black pouch with four vials of liquid and four small syringes. We would, we decided, keep my mother comfortable. Which, in her case, meant asleep. Awake, she'd chanted the mantra that had become a staple of her last few weeks I'm afraid. I'm afraid. I'm afraid. As she sunk in and out of sleep, the mantra came and went in fragments fraid...fraid...fred.... It fell to me, the physician, to squirt the color-coded anodynes into my mother's mouth: thick red for pain, ice blue for anxiety, vague pink for secretions. On the second day we switched on the machine. It made a beautiful, low, complex sound. There was a deep, continuous rumble, like a purr. Above the rumble there was a biphasic sound, much like breathing -- a hissed inbreath, and a longer, lower-pitched outbreath that began with an percussive note like a gently struck tympani.

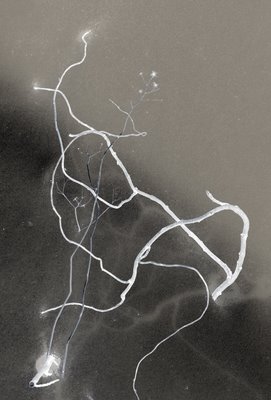

I didn't need blood tests to tell me what was happening and what would happen -- her pCO2 and Na+ would rise, metabolic and respiratory acidosis would set in, the BUN and creatinine would increase; I glanced at her foley bag -- urine output less than 30 cc's per hour. Officially oliguric. Undoubtedly she would, if she hadn't already, develop aspiration pneumonia. Finally, the K+ would rise -- her ECG's T waves would peak, the QRS complexes would widen, and v. fib would set in. That would be it.

What we saw was this: my mother's loud, quick, gurgling respiration suddenly, almost imperceptibly shifted, became slower, shallower. Our hands shot to her wrist. Do you feel a pulse ? I asked C., my sister-in-law. She shook her head. I looked at my mother's face and watched what little color that had been in it drain out. Then her breathing stopped. It was the sudden, complete pallor that surprised me, the sinking of her stalled blood. It was over.

We switched off the oxygen machine. The room was very still. It was 7:40 PM on Ash Wednesday.

Last Monday, five days later, my brother's car turned left and followed the minvan that contained my mother's body up a steep hill. Over the rise was a low building with several wide, metal-housed chimneys. The air above the chimneys shimmered like a heat mirage. We parked and approached the van. The undertaker and a denim-clad worker slid a long, slender cardboard box onto a stretcher. My mother's name was written on the top, in pencil. We followed the worker into a concrete corridor. On one wall were complex metal panels -- switches, buttons, dials, digital read-outs of temperatures. On the other wall were three retorts, two closed, one open. I peered into the open one, into a dark oblong space about three or four feet wide and tall, a space so dark it seemed for a second not a closed space, but a tunnel. I half-remembered an old, Lithuanian poem about the grave as a dark lodging without door or windowpane.

But there was to be no lingering to disinter poems half-buried in my brain. No, there was a box to ease into a hole, and a stainless steel door to latch shut. 55 years and 17 days prior I had slid out of the depths of my mother's body where I'd been woven, and here I was today watching my mother's body slide into the space in which her body would unweave. That long movement was more a vortex than a chiasmus; my spiritual acedie became tinged with vertigo. The worker invited us to start the furnace. Go ahead, said my father, nudging me toard the shiny panel. I hadn't prepared any words. I felt as if I were in one of those anxiety dreams, caught onstage in the spotlight with no lines memorized. It seemed so unceremonious, so clinical, but I pushed the button, red for ignition, and a muffled roar welled up behind me. I looked at the temperature gauge. It hovered in the low 400's. I looked away. There was nothing left to do. There was nothing to say.

There would be time for words, later. I knew exactly where to find the Lithuanian poem, and the outline of a eulogy was slowly taking shape in my mind. For the moment mortal flesh would keep silent: that would be our ceremony.

As we walked across the parking lot toward the car, I turned and looked again at the hot, shimmering vapor rising from the smokestacks. My Mother's present lodging, unlike the grave in the old poem, did have a door -- or at least an open skylight.

As a cold wind hit my face, I breathed deeply and got into the car.

No comments:

Post a Comment