Cette vie est un hôpital où chaque malade est possédé du désir de changer de lit. Celui-ci voudrait souffrir en face du poêle, et celui-là croit qu'il guérirait à côté de la fenêtre.Charles Bauldelaire, "N'Importe Ou Hors Du Monde." *

It was the hospital where she'd been born over half a century ago. High on a hill, it overlooked the crowded streets and abandoned mills of the industrial city to which her grandparents had immigrated half a century before that. The view from the first window had been sublime. Even amidst of the anxious events and vocabularies of medicine -- infarction, catheterization, ejection fraction -- it had caught her eye: the piercing blue of earliest evening, the old clock tower, long brick facades cinctured with light.

She'd wished she had her camera.

The view from the current window was more pedestrian: streets, rooftops, a steepled horizon. Between the first window and this one there had been other windows and other events. She thought of the word

hospital -- it meant guest house. A place of transients, of transit. It's where she herself had arrived, early, too small, in the dead of winter. 1952.

Sic transit, she supposed. At least she had her camera this time.

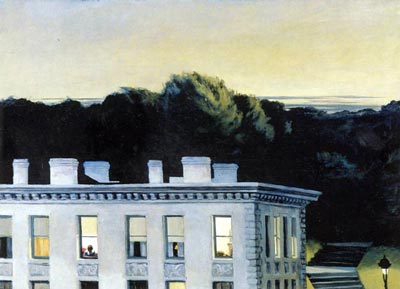

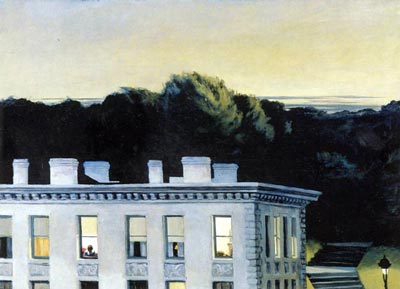

Downstairs in the hospital, between the coffee shop and the elevators, there was a long, bright yellow corridor. It was usually, peculiarly, empty. There were a few cheerful prints on the wall, reproductions of famous works of art, Van Gogh, Diego Rivera, and one, her favorite, that she suspected was by Edwin Hopper.

She stopped to look.

In the painting it is evening. There is light in the sky, the fleeting doomed kind. There is a bright stone facade, a boarding house perhaps; windows, some lit, some dark; a rooftop with long shadows. A streetlamp glows, and, beside it, a stone staircase leads upward toward black, shadowy woods. In one window a woman sits, gazing out. The woman is, she supposed, alone. Alone in the meager hospitality of the transient hotel. The sun has sunk below the horizon. There is pale, remnant light in the sky. Heaven will soon be as black as the earthly woods. Vespers, she thought. A time of day that cries out for prayers. Anything to posit against the terror of nightfall.

O phos hilaron.She hadn't slept through the night until she was three. As a child, she couldn't fall asleep unless her mother were awake, keeping vigil in the living room, sitting in the big chair beneath the lamp, reading, eating oranges. She'd slept with a nightlight until she was fifteen. The light in the yellow corridor hurt her eyes.

She took a sip of her coffee and headed toward the elevator. She'd sit vigil for awhile longer, beside the bed of the woman who'd been here with her for her arrival half a century before. Things were, overall, improving. The vocabularies were moderating: convalescence, physical therapy, rehab. New windows were forthcoming, and then, soon enough, the windows of

home.As she gazed out at the darkening afternoon, a song began to run through her head, a setting of a psalm by Orlando Gibbons. As a young woman, she'd played Alfred Dellar's recording of the beautiful hymn over and over until it seemed to become part of her own tissue. Even now she could hear the poignant, imploring inflections, the half sob in

sojourner before the melody thins and settles.

... for I am a stranger with thee

and a sojourner, as all my fathers were.

O spare me a little that I may recover my strength

before I go hence and be no more seen. It was a perfect lullaby.

*This life is a hospital in which each patient desires to change beds. This one wants to suffer before the fire. That one wants to heal beside the window. C. Baudelaire, "Anywhere Out Of The World."