Fissure

She had entered a deep and complicated forest, the kind in which the darkest fairy tales are set. She had a map, a tarp, a compass and a lamp, standard issue, she was told, all she would need for her journey.

Through study she had come to know the few things essential for survival: how to find true north, the names and usages of the most common weeds, and, of course, for water, divination.

The rest, she was assured, she would learn along the way, including how to read. There would be no rosetta stone, just blank rockface, crisscrossed with branches and bathed in light.

She departed in autumn, telling only one person about her journey, the one who would hear and wish her farewell and then forget everything.

She entered the deep, complicated forest. Shafts of sunlight pierced the pine canopy. There was music; the forest groaned and wheezed and creaked like an enormous windchest. She heard obbligatos of birdsong and glissandi of falling water; she felt the basso profundo of the earth turning beneath her feet. She hummed along.

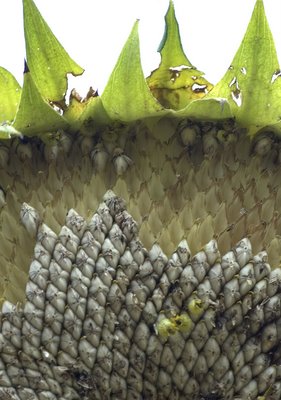

As her eyes grew accustomed to the light she realized she was not alone. There were others in the forest. Other -- what ? -- vagabonds ? Pilgrims ? They moved together as one body through the wind and falling leaves, reading the moving glyphs of leaf and light and wind.

It may feel like submission, she'd been told at the outset.

Yes, she'd agreed.

There were tracts, she knew, that laid bare the geography of the woods, stunningly beautiful schematics incorporating what once was and what would someday be. Her own map was smudged, and of questionable origin -- a squiggle here for water, a curve and a flurry of x's there depicting a hillside covered with trees. It was little more than a doodle on a cocktail napkin.

Some said that, beyond the forest, there was a beautiful city. Others whispered that the forest itself was that beautiful city. Still others said the forest was, improbably, a man. Or that the forest was two overlapping cities -- the one she had left behind, and the one she was approaching.

She understood overlapping. How leaving and staying can coexist. How a forest can be two cities and a man and vagabonds moving as one body through falling leaves.

And she understood this, too: that the deep and complicated forest was as ordinary as her kitchen, her workplace, the streets of her town.

As ordinary as a hardwood seat, as morning light through colored glass; as ordinary as lessons in a high-ceilinged study; as ordinary as teacher, priest.

The imagination said Simone Weil is continually filling up the fissures through which grace might pass.

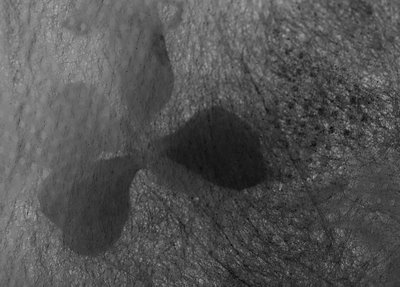

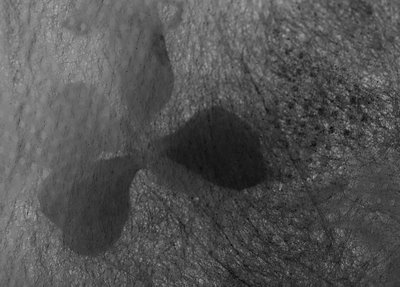

She thought of the two-hands-and-ten-fingers game her mother had taught her half a century ago: this is the church, this is the steeple; open the gate and see all the people !

She stopped in the middle of the forest path, interlaced her fingers inside the shelter of her palms. Overturing and opening her hands, she saw the people who'd taken her in, welcomed her, and fed her.

It was the first lesson, and the only map she'd ever need.

Through study she had come to know the few things essential for survival: how to find true north, the names and usages of the most common weeds, and, of course, for water, divination.

The rest, she was assured, she would learn along the way, including how to read. There would be no rosetta stone, just blank rockface, crisscrossed with branches and bathed in light.

She departed in autumn, telling only one person about her journey, the one who would hear and wish her farewell and then forget everything.

She entered the deep, complicated forest. Shafts of sunlight pierced the pine canopy. There was music; the forest groaned and wheezed and creaked like an enormous windchest. She heard obbligatos of birdsong and glissandi of falling water; she felt the basso profundo of the earth turning beneath her feet. She hummed along.

As her eyes grew accustomed to the light she realized she was not alone. There were others in the forest. Other -- what ? -- vagabonds ? Pilgrims ? They moved together as one body through the wind and falling leaves, reading the moving glyphs of leaf and light and wind.

It may feel like submission, she'd been told at the outset.

Yes, she'd agreed.

There were tracts, she knew, that laid bare the geography of the woods, stunningly beautiful schematics incorporating what once was and what would someday be. Her own map was smudged, and of questionable origin -- a squiggle here for water, a curve and a flurry of x's there depicting a hillside covered with trees. It was little more than a doodle on a cocktail napkin.

Some said that, beyond the forest, there was a beautiful city. Others whispered that the forest itself was that beautiful city. Still others said the forest was, improbably, a man. Or that the forest was two overlapping cities -- the one she had left behind, and the one she was approaching.

She understood overlapping. How leaving and staying can coexist. How a forest can be two cities and a man and vagabonds moving as one body through falling leaves.

And she understood this, too: that the deep and complicated forest was as ordinary as her kitchen, her workplace, the streets of her town.

As ordinary as a hardwood seat, as morning light through colored glass; as ordinary as lessons in a high-ceilinged study; as ordinary as teacher, priest.

The imagination said Simone Weil is continually filling up the fissures through which grace might pass.

She thought of the two-hands-and-ten-fingers game her mother had taught her half a century ago: this is the church, this is the steeple; open the gate and see all the people !

She stopped in the middle of the forest path, interlaced her fingers inside the shelter of her palms. Overturing and opening her hands, she saw the people who'd taken her in, welcomed her, and fed her.

It was the first lesson, and the only map she'd ever need.