Back Bay Station is a dark little joint, physically and aesthetically cold, and as grimy as one would expect from any midwinter, urban, public space.

The high windows don't admit much light, but I had a fast lens -- f/1.8 -- so I snapped away as I waited.

I noted with amusement the public redaction on a sign explaining the new "Charlie Card" system. Boston's subway, aka the MBTA, used to operate via coins and tokens, or commuter passes for frequent patrons. The transaction was simple. Give cash to a person in the booth, get a token, insert token in turnstyle, board train. Recently a byzantine system of "Charlie Cards" and "Charlie Tickets" was instituted (Charlie from the old song "Charlie on the MBTA"). This, as far as I can tell, involves touch-screen computers with a confusing array of coin or credit card options, a plethora of choices involving tickets and receipts, cards with "value" that can be added and subtracted. All, I suspect, to eliminate the ticket-taker's job. As I photographed the sign, I smiled at the small evidence of human dialogue amidst the ambient dehumanization.

For all this complaint, I must confess to a strange attraction to empty public spaces, the grimier and the more shadowy the better.

Underground, objects take on a stark and numinous singularity.

Shafts of light traverse the gloom as through dark water.

A brief flurry over the tracks -- a pigeon flies past.

I've always wanted to photograph the subway's catacomb-like tunnel wall recesses.

The train was nearly empty. I chose a window seat and settled in as the train left the station and entered daylight. After a while, a man sat next to me. He was courteous and quiet, about my age and carried a small brief case -- most likely a businessman. His friend sat across the aisle from him, and immediately began to talk. To expound and expatiate and recount, as in raconteur. My seat mate made intermittant noises of assent and encouragement as his friend went on and on. And on. I couldn't help listening. He spoke at length of parties, past and yet to come, of office politics, of colleagues, favored and suspect. Then he launched into a long story -- a much rehearsed set piece, I imagined -- of a hunting trip he'd been on two decades prior.

He was sitting, he said, on the side of a remote cliff in Maine looking down at a river so clear he could see the fish swimming in it. As he cradled his gun -- a large, powerful rifle -- he thought Even if I find no animals on this trip, there are such abundant fish in that river that I am guaranteed a kill ! The thought pleased him, he explained, for the purpose of the hunting trip, after all, was to kill an animal.

But soon he heard a crashing in the underbrush and he spotted the largest buck he'd ever seen, with a huge rack of antlers. He pursued the animal, and, eventually shot it. But it rose, wounded, and fled. There was a ethic to hunting, he explained. He had to find it and finish it off.

And, of course, he did; he slew it, and hauled the carcass miles through the snowy woods to the hunting cabin (with his brother who by now had shown up in the tale.) They gutted it, and butchered it. The tale went on and on: the cold, snowy night; the warm, cozy cabin; the Stoli, ice-cold from being stashed in the snow; the bellies full of meat.

It was a tale he'd told countless times, I was sure. I watched the landscapes roll past -- the reedy lowlands leading to the sea, the industrial wastes, the trackside dwellings of the poor.

The sun was sinking, and blinding.

Everything seemed low and mean and dilapidated and yet, at the same time, oddly beautiful.

These were the the timeless dwellings of human beings, their courtyards and clotheslines, their markets and city streets. Where lights come on at night to dispell the darkness, where tables are set and food is eaten, where lovers sleep side by side, arm in arm, where children play.

Where the light, just before twilght, is as ineffable and glorious as God, Himself,

where the color blue goes straight from the eye to the heart,

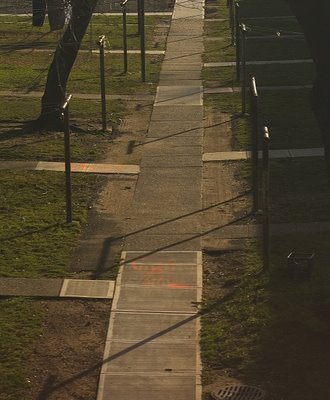

and where even the starkest, most faceless symmetries stand on the dusty ground with dignity.

The Acela alternately sped and crept through its landscapes. I squinted into the light

which reduced structures to silhouettes

and complex, illuminated glyphs. We were approaching the city, hurtling past

the bedroom towns of Connecticut. My seatmate and his friend had long since retired to the club car where I, myself, had also bought food: a bagel with butter and coffee with milk, both serious dietary trespasses for a vegan, forgive me Bossie: I could have forgone the milk they stole from you. I could have, maybe should have, been content with dry bread and black coffee,

but something about this trip, this week, this life cried con leche, por favor

and I could not help myself.

I cradled my camera -- a large, powerful Nikon -- as I watched the landscpe grow taller, starker and more industrial.

Soon I'd be in Manhatten, about as far out of my weedy, solitary element as could be. There, the air would be thronged with indecipherable messages; men in starched shirts and stiff hair would look through me, past me, their eyes on what prize I can't begin to imagine.

A wordless prayer fluttered in me, like a pigeon lost in a tunnel. I stared, and the wordless answer came, like wind through scaffolding, spirit into flesh.

Amazing, I thought, as we hurtled toward the city. Like grace.